TBC/MAG

Issue²

OUTDOORS

Jenny Kendler

Artist | Activist | Naturalist

Offering

By Eve Wood

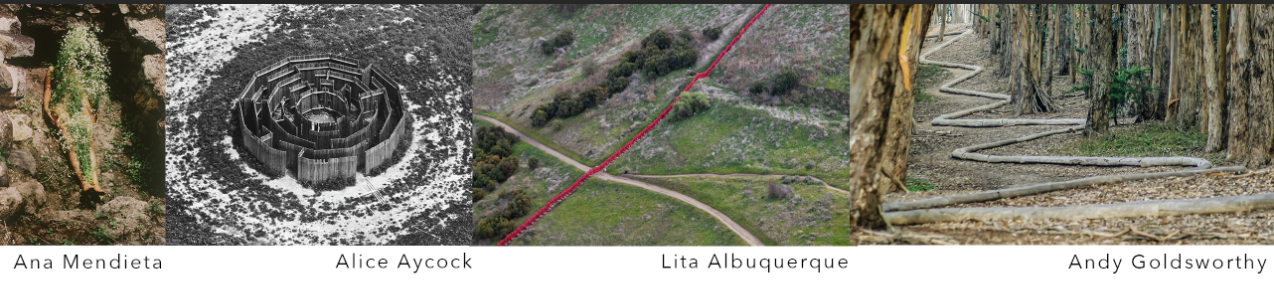

Jenny Kendler’s performative based artwork entitled “Offering” finds its roots planted firmly in the history of environmentally conscious art practices whose luminaries include Ana Mendieta, Alice Aycock, Lita Albuquerque, and Andy Goldsworthy.

Like these artists, Kendler’s interventions into nature are subtle and delicate and derive from a desire to understand our place in the natural world and our responsibility as stewards of the planet. Kendler sets up an alternate reality within the framework of a familiar and manmade natural occurrence, i.e. a hummingbird’s visit to a feeder. Kendler stages her own body as an alternate source of sustenance, having painted her ear a deep and enticing shade of red, and periodically filling her ear canal with sugar water, to attract the birds.

Kendler’s performance is less about the actual visitations of the birds, circling as they do around the feeder and Kendler’s ear, and much more about the artist’s commitment to her own process, standing still for two hours as the birds navigate the surrounding landscape. The work is a mediation between the human body and nature, an attempt to intersect the natural order of things, not for the sake of disruption, but for the sake of understanding. On the surface, Kendler’s performance appears quiet and simple, yet hers is a quietude that derives from an essential and undeniable longing for a better world, or at the very least a world where human beings are attentive to the beauty that surrounds them.

Kendler interjects herself into the landscape in much the same way Ana Mendieta allowed that her body was its own verifiable province, alive and flourishing alongside the living world. The interjection is low impact in terms of its actual physicality yet intensely realized in its deeper intentions. For example, in her Silueta Series, Mendieta mediated her naked body with the earth, creating female silhouettes in nature with materials ranging from leaves and twigs to human blood in an attempt to remake herself and repair her sense of displacement, having been sent away from her native Cuba at a young age.

Similarly, Kendler employs her own body as a passive vehicle for contemplation and resistance. The artist’s one red ear becomes not only a vessel whereby the hummingbirds might feed, but also becomes a kind of portal of transmutation. Painting her ear red is both a gesture of regeneration and violence as the ear is a means of feeding the bird yet also appears bloody and disfigured. As viewers, we also associate the human ear with language or the ability to communicate, i.e. to hear and be heard, yet Kendler’s ear obfuscates its own functionality until the ear becomes less literally anatomical and more a symbol of dissonance, a gaping red orifice where language and sound dissolve into sugared water. Whether or not the bird partakes is ultimately not Kendler’s objective. What is more important is the fact the ear is being proffered up as an alternative source of sustenance.

Kendler’s “offering” also conflates our human senses in that we expect to hear with our ears. Hearing is subverted once she fills her ear with liquid which then transforms the ear into a drinking vessel which then further relates it with the act of eating. The ear is offered up to us as viewers as a kind of sacrificial offering, a point of entry into consciousness, yet this consciousness is subverted whereby the single red ear becomes a talisman for grief and joy simultaneously. Thus, Kendler’s ear transforms yet again into an object of intense fascination. The ear becomes not only a symbol of thwarted communication, but also a symbol for the artist as Mother Earth and shaman, healing the world while also excising personal demons.

Ultimately, Kendler’s body is transformed into an activated landscape of agency and self-reflection as the ear hears only the small hummingbird feeding beside it; the artist becomes a witness to her own practice as well as to the music inherent in nature. She hears her own breath coupled with that of the bird as the rest of the living world simply falls away.

Brittany Ransom

Parallel Paths:The Bark Beetle and Human Infrastructure

By Allia Casey Parsons and Carly DeFilippo

In our increasingly politicized and polarizing era, art often provides a unique opportunity to reconsider our perspectives. With a genre-bending portfolio that spans psychology, technology and art, CSU Long Beach professor and artist-in-residence Brittany Ransom literally challenges us to see the world from a different viewpoint. In particular, her work with insects asks us to consider the parallels between manmade infrastructure and other nature-based systems. In doing so, we must consider whether we, ourselves, are as big of pests as the species we often seek to eradicate. She recently sat down with The Billboard Creative team to discuss her sources of inspiration and the evolution of her work.

You grew up in a blue collar, industrial town in Ohio. Can you tell us a bit about how you became interested in art and technology?

I’m originally from Lima, Ohio, which is a relatively small town—about 30,000 people. I was an only child, and as a kid, I spent a lot of time by myself outside. Even then, I was pretty insect-obsessed. My mom caught me hiding insects in a bug catcher in a closet when I was really little. I was also a big lover of dogs, so—like most dog owners—I had this desire to communicate with animals on a deeper level.

When I went to Ohio State for college, I had no idea what I wanted to do. I thought I might want to be a psychologist, so I enrolled in all these advanced courses. One of them was a primate psychology class, which was really transformative for me. The professor was training chimpanzees how to respond to emotion and to communicate with us through a computerized interface. That was pre-iPad, but they had touch screen systems that let chimpanzees say whether they were sad or hungry—and I had this realization that while I was kind of interested in psychology, I was really interested in the devices we were developing to communicate with animals.

During that semester, I changed my major to art and technology. My parents weren’t thrilled, and the program was relatively new, but we learned how to utilize electronics, kinetics, animation and a little bit of 3D modeling. The two faculty members that ran the program were artists that worked with natural- and animal-based systems, so it really awakened me to what interested me as a psychologist, a technologist and an artist.

From there, I went to grad school in Chicago. The artists whose work interested me the most were based there, and the University of Illinois at Chicago had particularly strong programs in electronic visualization, kinetics and electronics.

When did working with insects, in particular, become part of your work?

Toward the end of my time as an undergraduate, I started making work with pests. Growing up in a place where farming is a big part of life, I was really aware of pesticides and pest-based systems. As a society, we spend millions of dollars to eradicate insects, so I started making work about humans being the biggest (or potentially biggest) pest-based system on earth.

One of my first projects let cockroaches control sound—they traveled through a tube and when they passed certain points, they would produce a sound. The idea was to give these insects a sense of agency. From there, I started making work with different pest systems: termites, cockroaches, ants— basically anything that people didn't want to be a part of our environment.

Your most recent project focuses on bark beetles. Where did that begin?

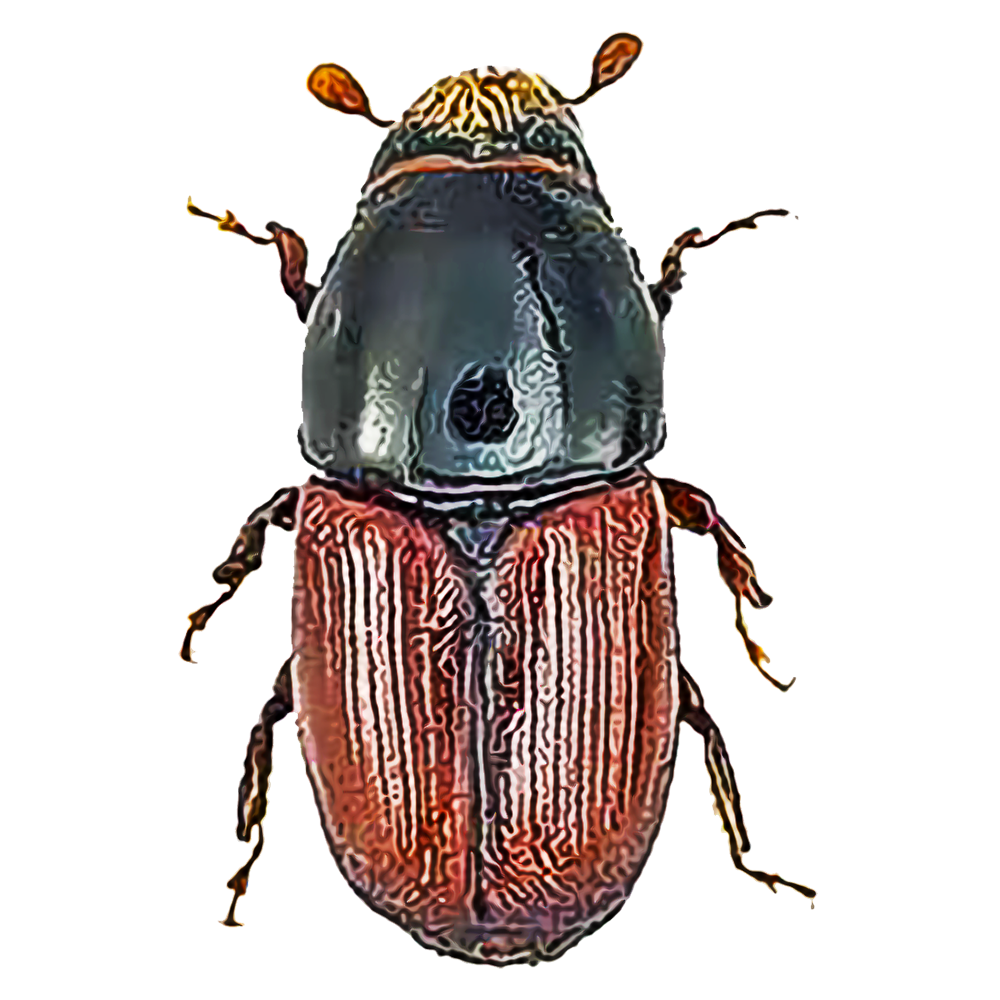

I was hiking in King’s Canyon and found these pieces of bark in a cleared area near a bunch of dead trees. I couldn’t stop staring at the patterns on them—it was like a Cy Twombly painting paired with a highway map. At the time, I was generally familiar with bark beetles, but had never done any significant research on them. It was my first introduction to a pest problem in L.A.—other than, say, houses being infested with termites or roaches.

From there, I started researching the impact of bark beetles on wildfires. In times of drought [when trees are weakened], their populations grow, and it’s harder to eradicate them. As a result, they kill more trees, which leads to more damage during the fire season.

What interested me most was all of the little paths the beetles make under the bark. When the tree is still standing, you have no idea that this system is being carved underneath it. It’s only once the tree dies—and the bark falls off—that you can see this really bizarre thing.

In the exhibit, you liken the paths created by the bark beetles to our own highways in Los Angeles. Why did you make that choice?

When I was finishing grad school, I worked on a project in which I tried to get termites to eat a city map of Chicago along the [path of the] roads. So [the bark beetles] were a moment of circling back to that project and wanting to explore it further—in thinking about the systematic ways that we build things verses the potentially systematic way that pests build things.

As humans, we construct things, plan things, take resources—and it’s a type of scarring. We’re moving and shifting material that we can’t get back. So I see humans in the same kind of metaphorical space as these beetles—making these paths, consuming these trees—and the impact is irreversible, both in their particular ecosystem and in our larger ecosystem.

I’m always trying to drop subtle—or not so subtle—hints to help viewers understand the larger concept of the work. If you can’t get someone to engage in a visual language, you’re not going to get them to engage in a conceptual conversation. So for this upcoming show, there’s a map of L. A. that's abstracted on the floor, and there’s a little car that follows an inductive line. I chose to have it trace the highway system, because—even as a novice art viewer—you can recognize this city. Hopefully, that’s enough to get someone to consider what the work might be about on a deeper level.

Your work frequently skews perception of scale, what does this achieve as an artistic method?

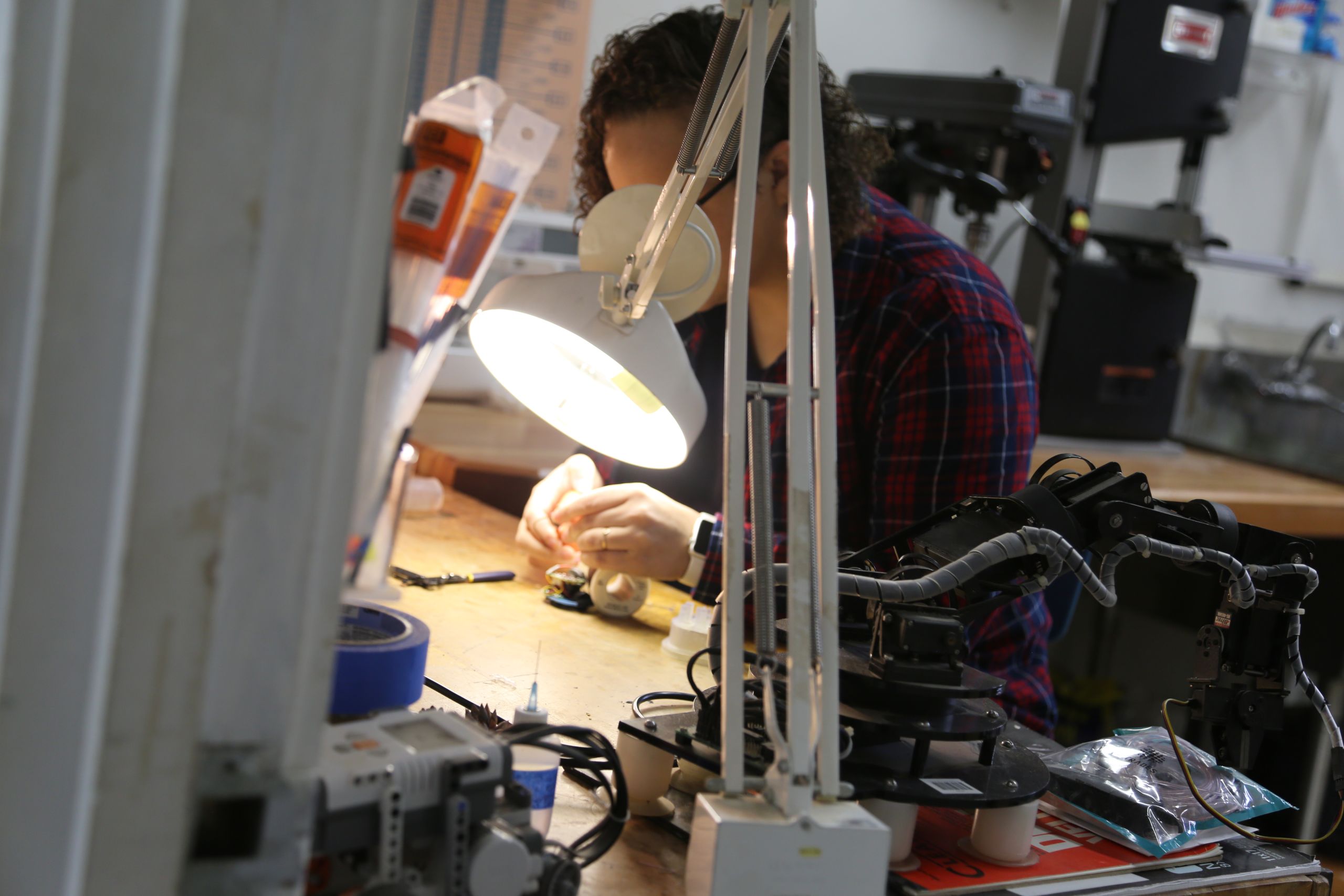

Shifting scale can be a powerful tool that allows us to understand systems differently. In my work, I utilize scale as a method of unveiling and find it critical to building a relationship between our body and smaller bodies (insects, in this case). I often play with scale to emphasize our human size versus that of smaller systems—magnifying the pest-like tendencies we have or blowing them up to almost comical proportions. I also utilize scale to explore notions of guilt that we carry (particularly in an older work, Fossilized Guilt) and also to maximize or re-organize ideas of impact. In this particular series, the work shifts from bark beetle-affected wood enlargements to actual size specimens that I 3D scanned and reproduced to their exact scale. I also use ultraviolet pigments and lights to illuminate what might otherwise be hidden beneath bark—or even at our feet—when we walk in our local parks or forests.

What is the effect and intent of making work about the disconnect between humans and their environment? And what is the benefit of creating this work using advanced technologies?

The intent really boils down to encouraging individuals to reconsider how they view themselves within a larger human system and how our system relates to non-human systems. I am interested in creating metaphorical links through objects, allowing us to reconsider ourselves through the greater lens of the natural system we are part of. In reality, humans are a small blip in the timeline of planet earth (as far as we know currently). Using advanced technologies allows me to utilize tools that many of us know well (cell phones for example) or recognize (3D printing) and to use them as material vehicles by which to share these ideas.

Do you find working with advanced prototyping technologies to be a limitation in exploring natural phenomena?

Evolving technology has always been at the forefront of my artistic, educational and professional career. While I am interested in emergent technologies and systems, it is imperative that my work calls to mind traditional sculptural techniques. For that reason, I rely heavily on the use of wood, plastic, metal and foundry processes, and it is imperative that these materials and methods make themselves evident to the viewer to provide a sense of tangibility. I simply see and approach digital fabrication technologies as a tool and material within my practice, the same way that I approach traditional materials and methods.

I think there is an assumption that using computer-aided systems will lead work towards a process of quick perfection, which couldn’t be more opposite. For me, working with digital software and tools requires the same type of dedication to skill and technique as working with most other materials. While the computer and computer-aided tools can do amazing things—sometimes quicker than analog processes—they still require a significant amount of time to process, assemble and prototype. I really see my use of these tools as collaborative, and I always have to adjust for the digital tool’s limits. Overall, I find these processes to be freeing rather than limiting. As these tools shift and change, I see an exciting opportunity for my practice and processes to evolve alongside new technologies.

Where do you see your work going next?

The title of my next project—Well, Real Estate Is Always Good As Far As I’m Concerned—is a quote from 45 (President Donald Trump) prior to election. This is an in-progress project utilizing a digitally fabricated wood composite city, which is constructed for the consumption / destruction by a colony of live termites. The entire city will be comprised of real estate that has ties to 45. Currently this includes 33 notable locations (the number may change) that I am 3D modeling based on images and information from Google Maps.

In its planned final form, the city will include small-scale models that reference famous high-rise structures, a university, golf course, skating rink, restaurants and performance centers that all refer back to 45’s real estate portfolio. This project is currently in its infancy, with the 3D models for each real estate structure being created through modeling software. After the buildings are modeled computationally, they will be 3D printed. After they are printed, I will make a mold of each city block and ultimately cast them in a custom wood composite material, allowing for the city to become a habitat and meal for a small colony of termites.

The city will be contained within its own acrylic dome, with proper considerations for the livelihood of the colony to complete the habitat. The dome is meant to reference the 1998 movie The Truman Show, a satirical science fiction movie where the main character is adopted and raised by a corporation. This character is also trapped inside of a simulated television show, which is intended to reference our current political climate and its rise to arguable popularity / power through network television. The city will be monitored with a live web camera feed to monitor the activity of its inhabitants.

I am looking for an entomologist to partner with on this project, to ensure the survivability of a termite colony—as well as the long-term hope for consumption of this dystopian city. I have been working on this project consistently for two years, and am somewhat nervous of its reception, but have always been interested in building a city for termites. Given our current political climate, it seems like the right time and opportunity.

The Elusive Beauty

Of Allison Tyler

By Eve Wood

Land art, or Earth Art as it is sometimes called, was an art movement that emerged in the late 1960s into the 1970s that used the natural landscape to create site specific artworks designed to expand boundaries by the materials used and siting of the works. How these works were encountered by viewers was a central component to their deeper more metaphorical meaning. The art movement known as Land Art rejected the commercialization of art making, embracing in its place a burgeoning ecological movement. One of the most important elements to consider when looking at and discussing this kind of work is its impermanence, and the idea that transience, mutability and decomposition are central to our understanding of the world and our place in it. Where most art presumes immortality, fetishizing objects to an exalted status and placing them in galleries and museums throughout the world, Land Art speaks directly to the insubstantiality of life and our fragility as human beings. The way in which we encounter these works determines the essence of their meaning.

Artists like Robert Smithson, Richard Long and Nancy Holt have spent decades intervening into the natural landscape slowly, poetically, incidentally, making small and seemingly insignificant gestures to alter the natural world. More often than not these interventions are not meant to last, but are temporary and largely experiential. In keeping with this traditional, Allison Tyler creates beautiful ephemera from tiny twigs and branches, constructing these elemental sculptures in the trunks of trees, on solitary logs and in places we as viewers might not think to look.

Again, the point to making this appears to be the act of intercepting the natural order of things, if only for a moment. Furthermore, looking at these works one has the sense that their existence is not insignificant despite the fact they vanish soon after they are made. It brings to mind the famous philosophical thought experiment whereby if a tree falls in the forest and no one is there to hear it fall, does it make a sound? I think Tyler would argue that yes, it does make a sound because it’s not the tree’s falling that distinguishes it, but the fact the tree exists at all.

Tyler’s sculptures anticipate decay in the best possible way. Their simultaneous fragility and decomposition suggest our own human relationship to the natural world, and her attempt to intercede, to transform, if only for a moment, such a small and limited area be it a tree trunk or a leaf, mimics our all too human desire to control the world around us, or to believe that we have such power as to influence the laws of nature.

In another sculpture, Tyler creates a work on the forest floor, small twigs and pieces of bark strung together to create an image that resembles the wing of a downed bird, or the remnants of some prehistoric creature long gone under. It is both a strange object in and of itself as well as a metaphor for death. This work in particular holds within it the notion of death and life existing simultaneously within a single and singular object.

Of course, in the end, Tyler’s sculptures are really small mediations as she continues to manipulate these natural materials, exploring their inherent possibilities for transformation even as they fall apart. Andy Goldsworthy once explained his interest in utilizing the natural landscape as his preferred material, saying “You must have something new in a landscape as well as something old, something that’s dying as well as something that’s being born,” intimating that the process of creating anything is circular, as with the earth itself – and that an extraordinary and necessary collision happens when both the elements of death and life are present within the work. Tyler understands this involvement intimately as her materials suggest something that has already passed -- bark, dried twigs, dead leaves, contrasting these elements against the all-too-human hunger to create.

Debra Scacco

Reveals the untold history of the LA River

By Allia Casey Parsons

Debra Scacco is an LA-based artist, curator, and map-maker who describes her work as a study of “lines of lineage, lines of passage, and lines of policy.” She examines how lines of permission impact people and policy, weaving together subjects of history, culture, and the environment. Thematically, her work spans from personal investigations into her own family’s immigration to broader inquiries about climate change, and most recently the Los Angeles River.

When Scacco moved to Los Angeles less than a decade ago, she noticed that Los Angeles had a very different relationship with the river. Having lived in New York and then London, she was accustomed to cities defined and united by their rivers, whereas Los Angeles was defined and united by its freeways. Scacco’s initial curiosity has resulted in years of ongoing research and exploratory works probing the known and hypothesized boundaries of the river.

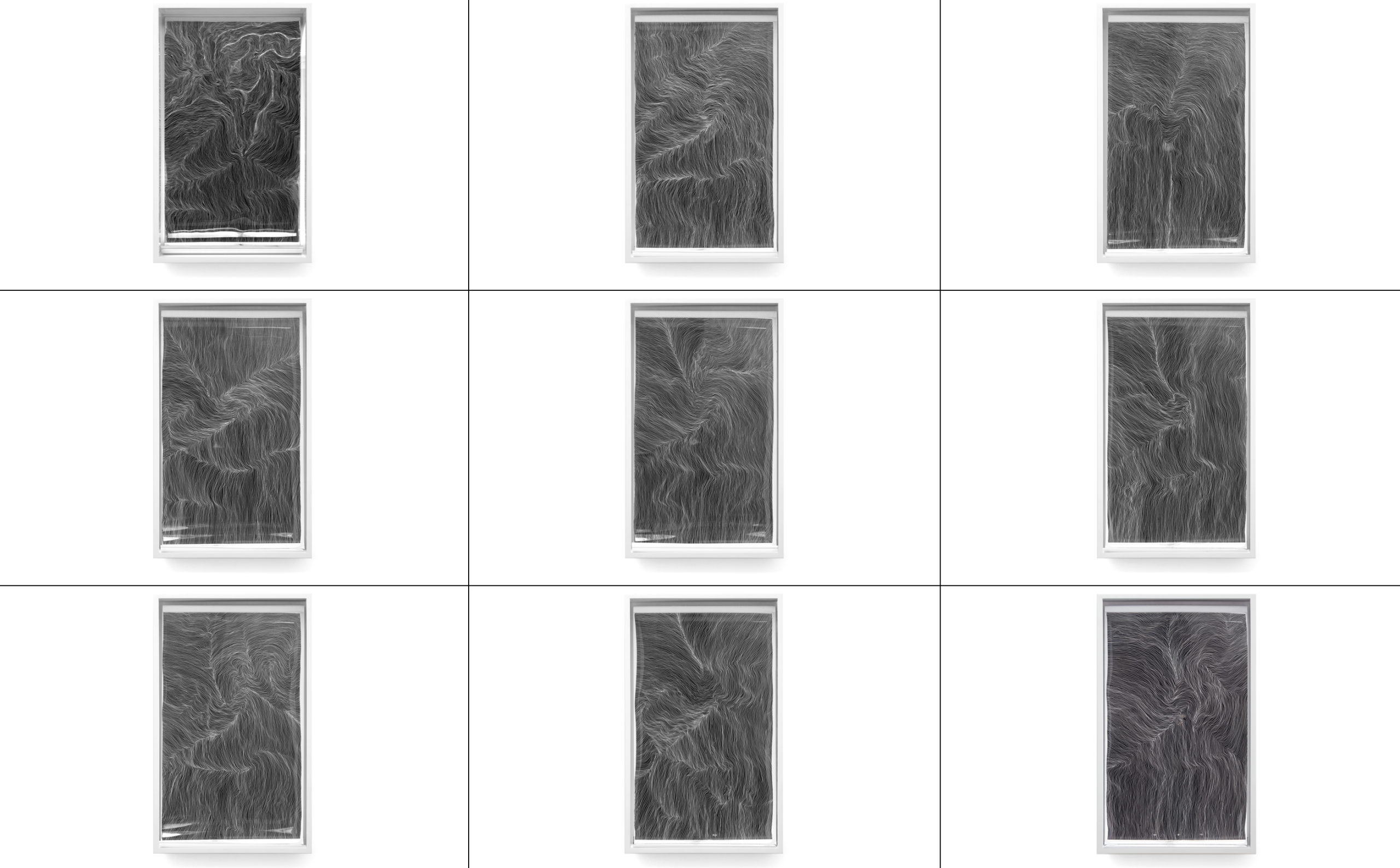

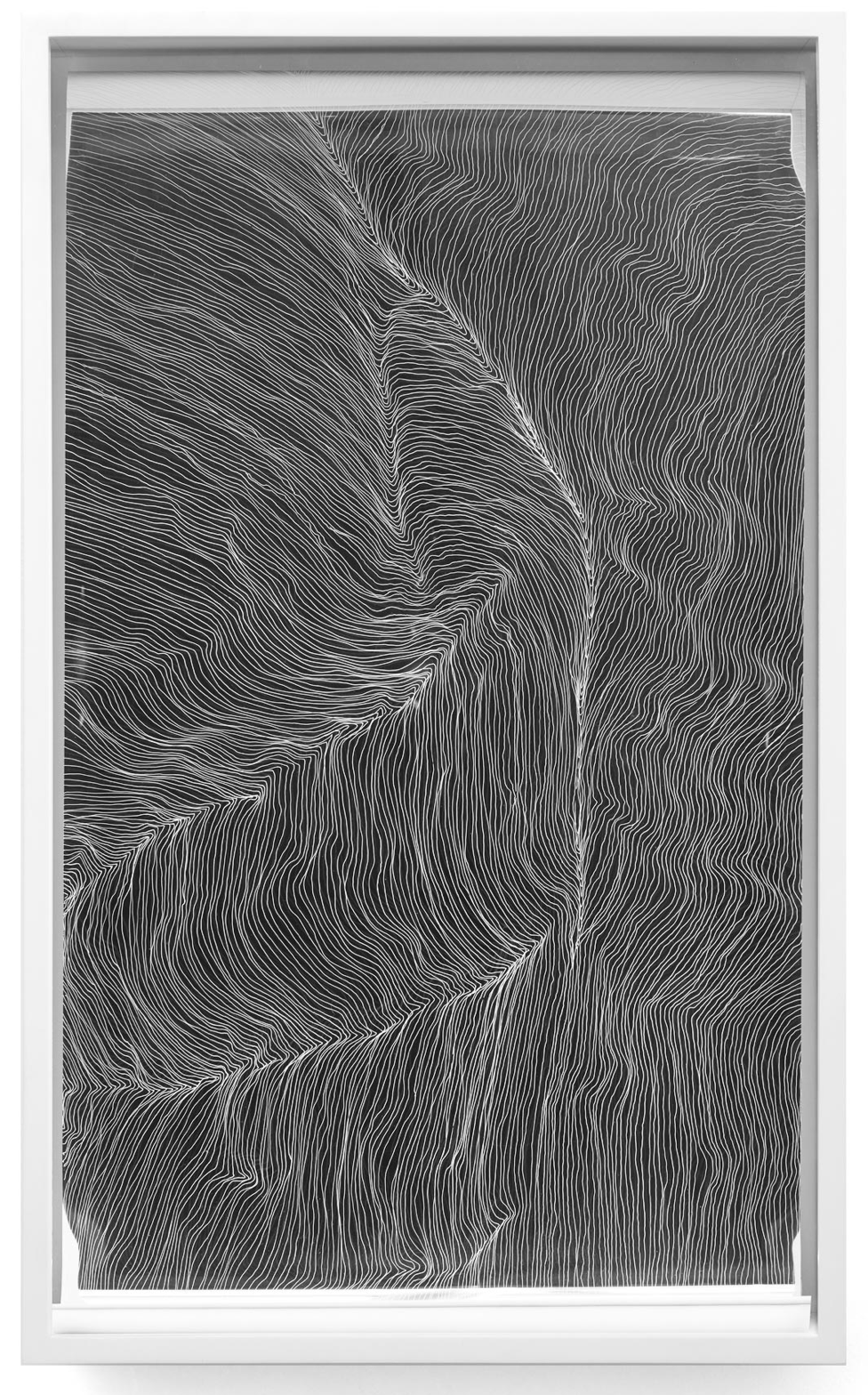

The Tributary Works are a series of drawings on mirrored panels isolating the path of each tributary as it flows into the Los Angeles River. Beginning with a line drawing of the main artery of the river, each work adds one tributary in isolation. With each line emanating out from the last, the body of work depicts the difference in current a single line can make. The series is an investigation into our lived environment, reflecting the observer as the most noticeable interruption into the once natural flows.

Los Angeles River (Artery)— Ink on Duralar 31 x 19 x 5.5 in

Los Angeles River (Artery)— Ink on Duralar 31 x 19 x 5.5 in

Los Angeles River (Rio Hondo) — Ink on Duralar 31 x 19 x 5.5 in

Los Angeles River (Rio Hondo) — Ink on Duralar 31 x 19 x 5.5 in

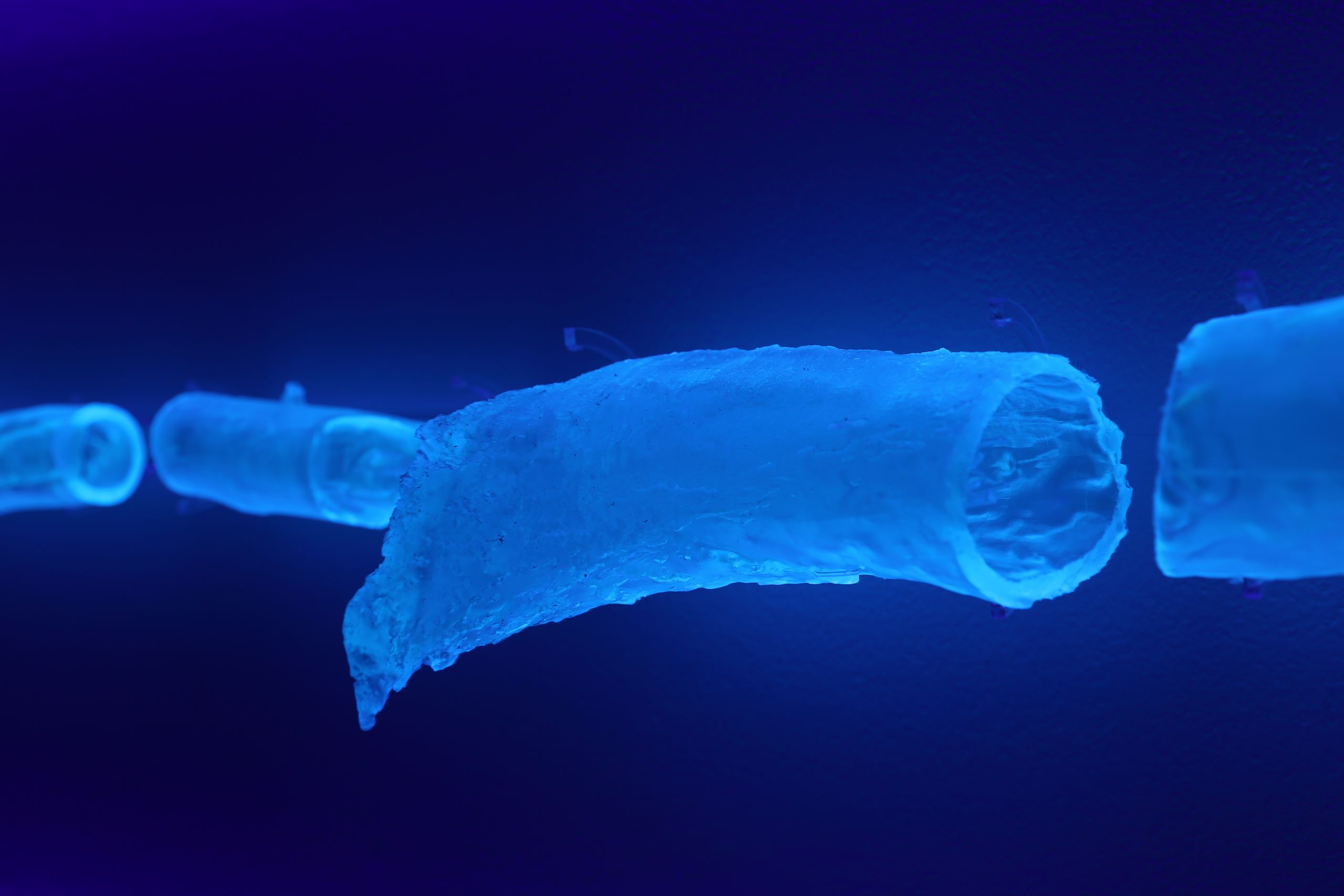

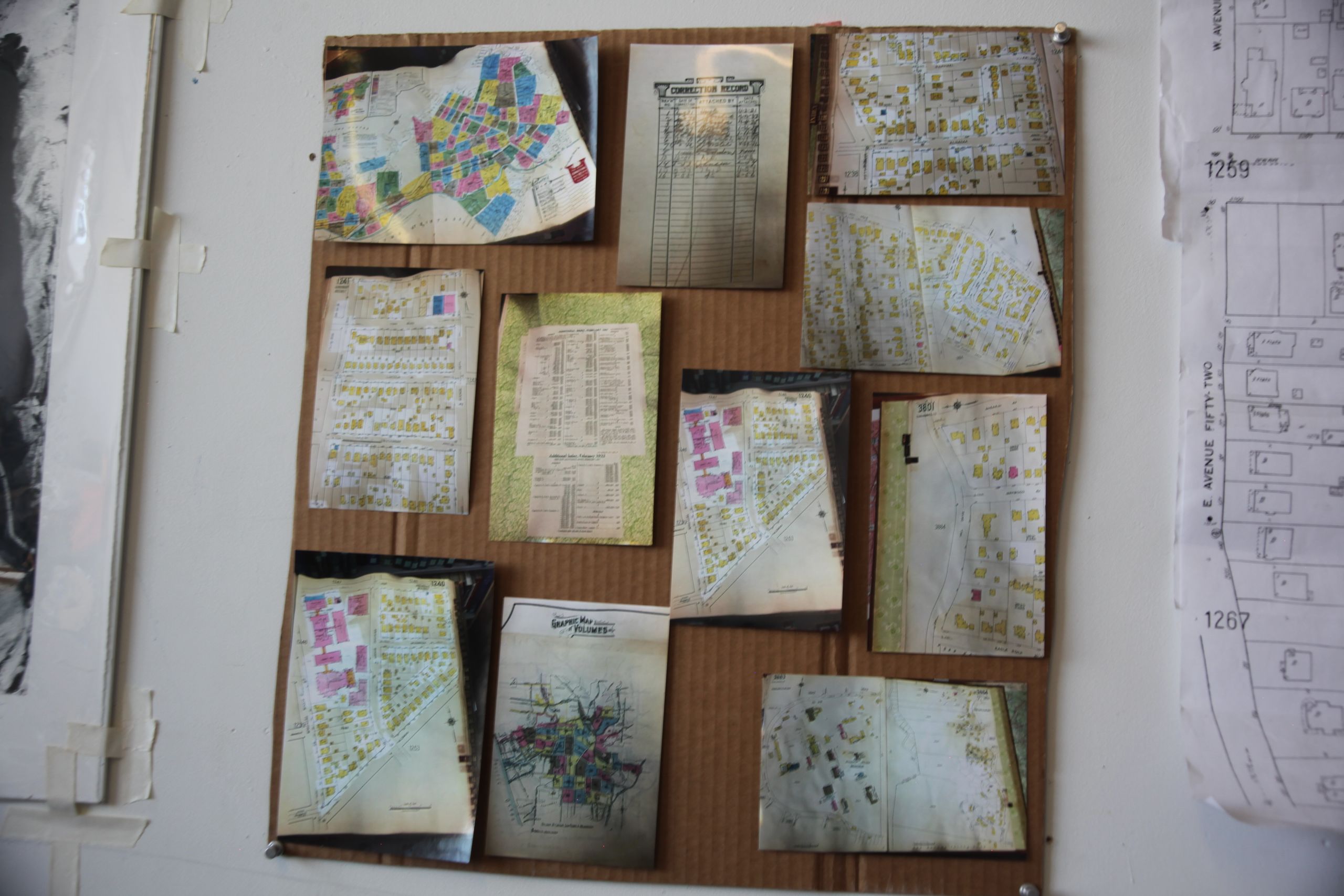

Approximations of History reveals distinct changes in the river’s course that led to this paved over dry-bed, representing the nine hypothesized courses between 1815 and 1938. The work presents a less palatable story of Los Angeles, one in which the life-giving river that had sustained Indigenous peoples for thousands of years prior was violently colonized by settlers who would eventually form the concrete basin, implanting a system of water scarcity into the heart of young Los Angeles.

Approximations of History

Approximations of History

The installation, comprised of nine sculptures each referencing a historic course, falls loosely in line with form of the channelized River. Walnut pedestals are topped with glass encasements, each containing a false fossil: a concrete slab derived from extracting the line of a previous course. Presented in a museological vernacular, the work questions the histories we have been taught, and the methods used to convey information as absolute and true.

Approximations of History is as much political as it is visually striking, questioning what our culture deems worthy of fossilizing as historical fact. Reckoning with history is necessary context for the severe water shortage we have today. Encased fragments of this waterway atop museum-like wooden podiums are ominous; a foreboding warning of what’s to come once drought becomes too severe and rivers turn to outdated relics.

“ I hope to strike emotional chords with people as they experience the work... creating opportunities to connect on a deeply personal and emotional level with issues that impact us all ,” said Scacco. “On a grander scale I want to contribute to genuine social and political action. I believe this begins with full access to the truth of our collective history. My work is a social commentary of the many unknown histories that led us to this moment.”

The upcoming Procession, slated for 2021, is a project utilizing mapping as a tool to mobilize historical knowledge, and to create a shared embodied experience. Physically tracing previous river courses mapped onto current day Los Angeles, the day-long event will begin with three groups of local residents traversing previous routes of the Los Angeles River based on maps of aggregated historical data. The groups will converge in a festival about water and ecology at Los Angeles State Historic Park, located in Los Angeles’ Chinatown, a location where historic river routes intersect. The festival indicates the expansion of Scacco’s practice. Through deep collaboration and engagement, she hopes to create experiences that inspire us to think differently about the river, and to be dedicated stewards of the water and the land in which we live.

The Narrows

The Narrows

“This is the best way I could think of to collectively experience this history of the river, and to reframe our relationship with the streets we walk on and the environment that we live in,” said Scacco. “Much of my work is based on knowledge that is generally locked away in archives. I am interested in breaking down the barriers presented by the walls of institutions, and sharing this information as widely and publicly as possible.”

In their own compelling ways, each of these projects documents the phases of man-made disruptions that transformed a natural resource into a concretized dry bed. In this telling, the river’s story becomes emblematic of the short sighted approaches to rapid urbanization of the early twentieth century that are at the heart of the climate crisis.

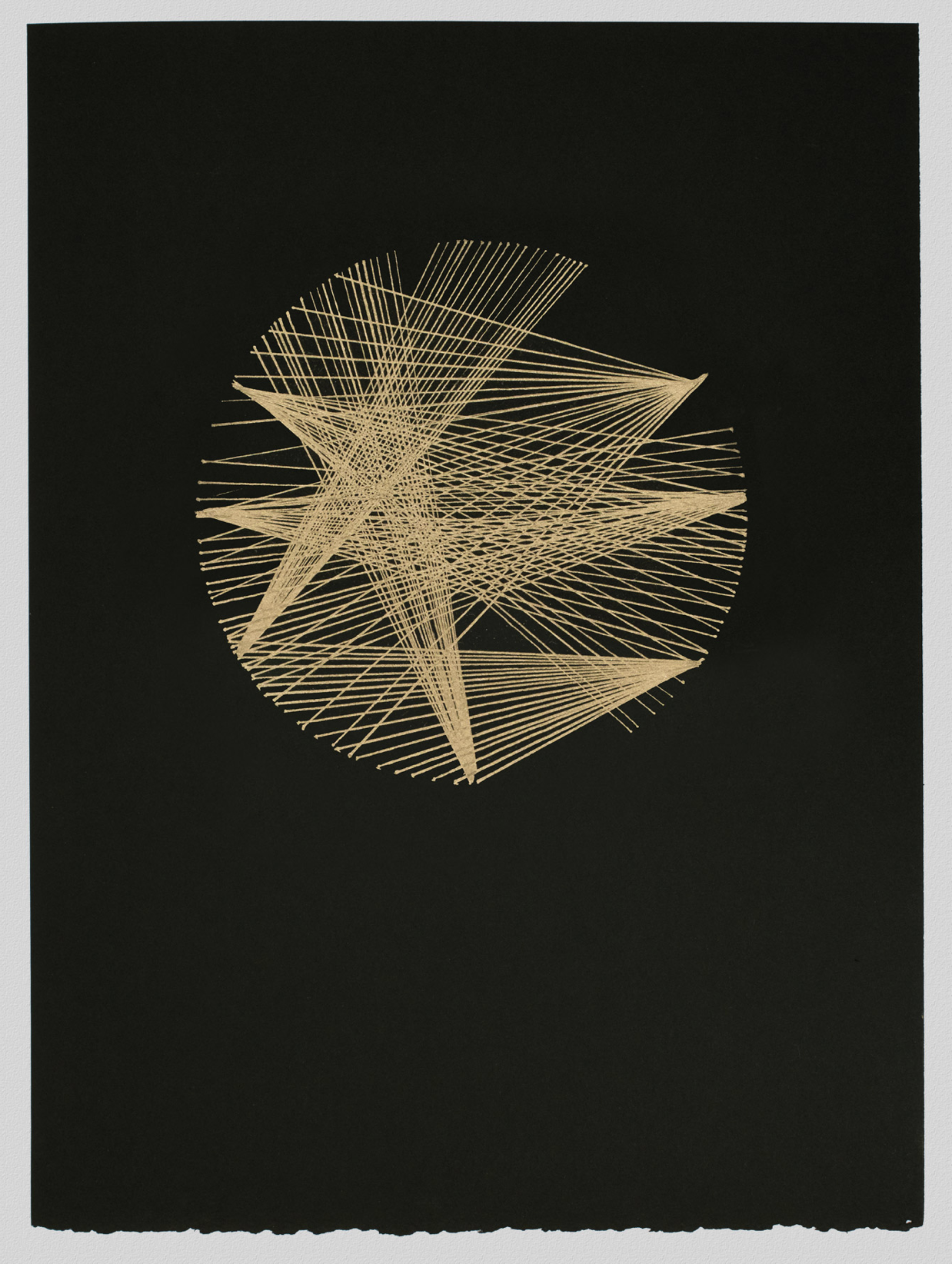

The Letting Go I — Metallic ink on paper 8.5 x 11 in

The Letting Go I — Metallic ink on paper 8.5 x 11 in

Scacco’s work comes at an important juncture in the life of the River. As architects, writers, activists, and artists turn their attention to the River and consider ways to bring new infrastructure and visitors to this long-overlooked natural feature of Los Angeles, there is a likely threat that residents in neighborhoods near the river will be pushed out in the name of “revitalization.” Scacco hopes that her work and it’s critical reflection on the River’s long history will contribute to shared knowledge and local participation efforts so that we do not repeat the same mistakes from the past and create a future that is socially and environmentally viable.

Kirsten Stolle's new project "Pesticide Pop" becomes a coloring book.

In her latest series of photographic prints titled “Pesticide Pop,” Kirsten Stolle entices us with bright and shiny colors subversively asking us to question what we are being sold and to examine our relationship with consuming. The artist centers photographs of pesticide bottles, mass-marketed weed killers developed by Monsanto and found at the local hardware store, on fields of electric pinks, energized blues, and intense yellows. Seduced by the glitz and the glam, we are taken in by Stolle’s absurd attempt to treat toxic weed killers as objects of desire.

As with her other projects like “No Genetic Dumping Allowed,” which “co-opted the structure of a municipal safety sign, replacing the ubiquitous phrase ‘No Dumping Allowed,’ with ‘No Genetic Dumping Allowed,’ warning against uncontrolled GM technology,” Stolle is warning us against the dangers of these toxic pesticides, but she is also asking us to look more closely at the world around us, and not to simply blindly accept what we are given. Ultimately, she is asking us to be more proactive in our approach to nature, considering how these manufactured chemicals affect our bodies and our environment.

The most significant element, aside from the garish colors, that links Stolle’s work to someone like Andy Warhol is the fact these works are ultimately a scathing commentary on consumerist culture. But Stolle takes this a step further by inviting us to participate in her work, creating alternate points of access for us as viewers. For example, with her Pesticide Pop coloring book, viewers are invited to print out black and white images of these same weed killers, coloring them in for “hours of fun.” This is a gesture steeped in irony – that we feed our kids foods that are chemically treated, in essence, slowly killing them, while they, innocent and sweet, lie on the floor with their crayons, filling in the world as they see it.

BONUS: Stolle included her Bayer-Monsanto Scramble! word-search puzzle. Hint: some words are backwards!

Kirsten Stolle

is a visual artist working in collage, drawing and installation. Her research-based practice is grounded in the investigation of corporate propaganda, food politics and biotechnology.

TBC / MAG

is a platform for emerging and mid-career artists. It is a semi-annual digital publication for curators, galleries and art enthusiasts. We are an extension of The Billboard Creative, a nonprofit platform for both emerging and mid-career artists. We work to help artists breakthrough traditional career bottleneck, providing unprecedented exposure to a mass market, by transforming commercial billboards into public art sites. This representation both raises the profile of individual artists with the general public, and introduces new works to curators, galleries, and passionate art enthusiasts.

FOUNDER/EDITOR: Adam Santelli / Kim Kerscher

SUBSCRIBE / SUBMIT: thebillboardcreative.org

COTACT: asantelli@thebillboardcreative.org

INSTAGRAM: the_billboard_creative

TWITTER: @tbcbillboards

All Image copyrights are held by the Artists that created them.