TBC / MAG

Issue 1

1. SKID ROBOT INTERVIEW 2. KIRSTEN STOLLE 3. JUDY LIPMAN SHECHTER + DAVID SHECHTER 4. LISSA RIVERA 5. CHEE-KEONG KUNG 6. MARGERY THOMAS-MUELLER 7. GEIR MOSEID 8. SEAN GALL 9. BERNADETTE DESPUJOLS

1

Skid Robot

Words By Carly DeFilippo

INTRODUCTION

If you live in Los Angeles and have an interest in street art, chances are you’ve heard of Skid Robot. With his creative juxtaposition of art and the daily struggles of the homeless community in downtown LA, his work takes us back to a time when graffiti was primarily a political outlet—a way to hear those who don’t traditionally have a voice in society. At a time when art increasingly looks like curated installations in closed galleries, Skid Robot’s work depends on the gritty, chaotic realities of city life. We sat down with the artist to learn what drives his work and what he feels modern street art has forgotten about its roots.

How did you get started in street art?

Before Skid Robot, I was already doing graffiti with friends, but I wasn’t happy with the explosion of street art and how it had lowered the bar of artistic quality over all. In particular, certain graffiti artists would plagiarize other people’s work and pass it off as their own—and that was increasingly accepted. I also wasn’t interest in doing stencils or posters; I wanted to produce something more than simply my own tag or my crew’s name.

I was discussing all of this with the girl I was dating, as pulled up to a light on Skid Row. She looked over and said, “Why don’t you paint that [homeless] person like they are dreaming of money—like, we all want to be rich.” So I jumped out of the car with a spray can, and when I pulled back to take a photo of what I had done, I just had this feeling of “this is it.” It’s one thing to have an idea, and another to take immediate action on it. I just became hyped on the concept, and started sharing my work on Instagram, which is how most people came to see what I was doing.

Your graffiti isn’t traditional or two-dimensional, in that it interacts with a living, breathing community. How has that relationship developed over time?

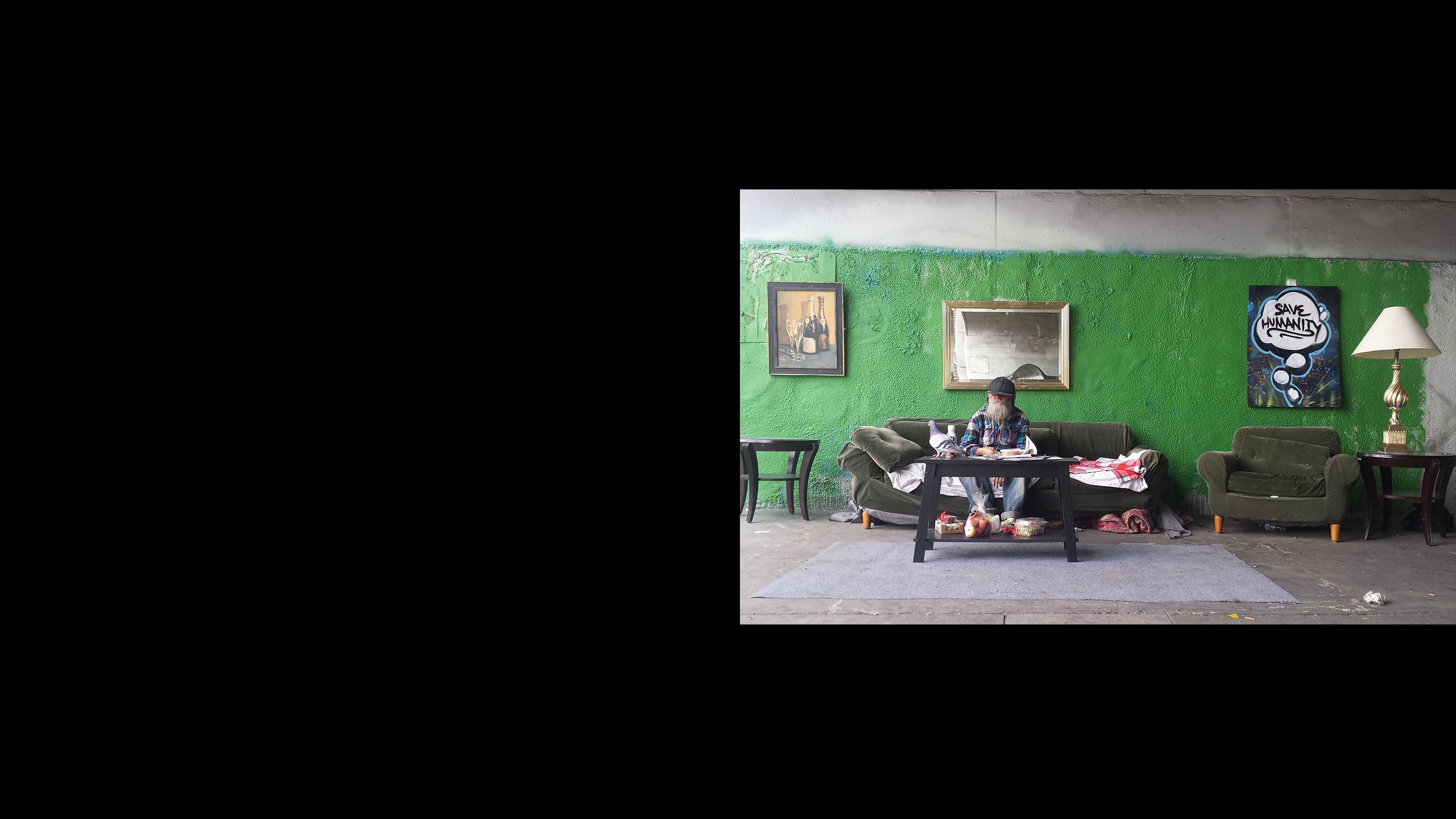

When I turn a corner and see the tents of the homeless population, I’ll think, “Those tents belong in the mountains.” So I draw a forest of pine trees. When the individuals living there see my work, they’re generally with it. We end up having a different interaction than they are used to, and it’s led to me getting to know the community and understanding that many of them are okay people. From the perspective of outsiders, I think it becomes humanizing as well. We all watch movies where we can relate to fictional characters [whose circumstances are different than ours], and I think my art provides a sort of similar frame—only in reality.

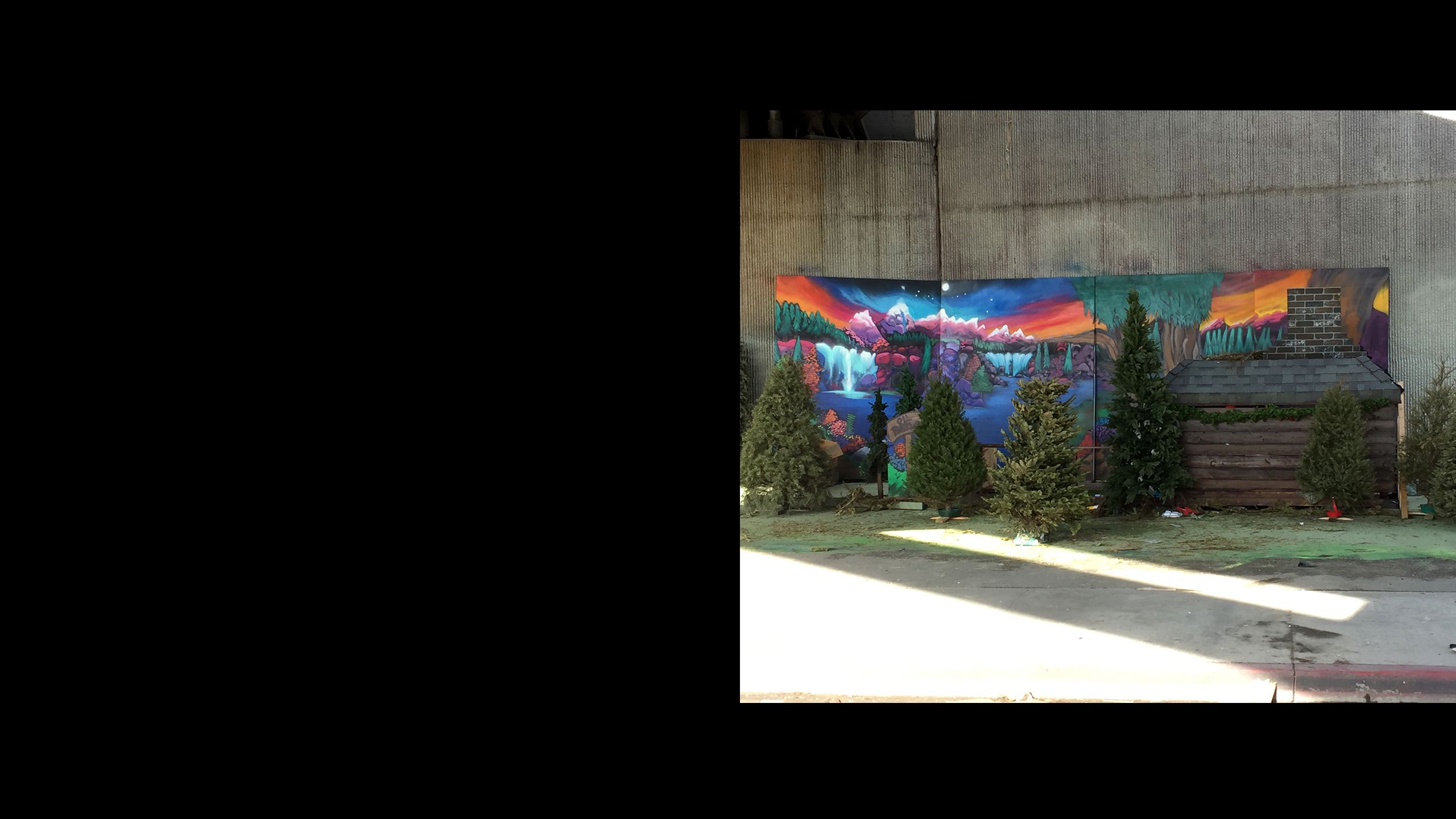

Why do you think your art helps people view the homeless in a more compassionate light?

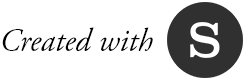

We are all born and gifted with the power of our imaginations—to pretend or make believe. There were a series of thrones I painted, which I called “A King Without a Castle.” To me, that’s about the fact that every life is divine and precious. If we really learned to value ourselves and the lives of others, we wouldn’t allow people to end up in these situations. The juxtaposition of my art with the gravity of these situations creates sort of a mirror—a space for compassion.

You’ve also gone past traditional graffiti to creating larger installations around Los Angeles. Can you tell us about the cabin under the bridge, for instance?

That was “Old Rusty’s Cabin.” When I first met Rusty, he was living in a place full of garbage. I wanted to do something in that location for years, and at some point, the city had cleaned everything out, so I took that opportunity to go talk to him again. What I initially made for him was a living room, and through that, I was able to drum up support to get him a few nights at a hotel through my following on Instagram. But ironically, Rusty didn’t want to go. He isn’t someone who doesn’t have family or a place to live. He’s one of nine siblings, but to him that bridge is home. That’s where the idea of building the cabin came from—bringing home to him.

I actually built another tiny house under the freeway for Birdman, but the city came and bulldozed it. I went back and tagged the site with the mayor’s Instagram handle, posting the image to social media with the phrase, “You can take a man’s house, but you can’t take his spirit.” That was mid-afternoon, and later that night, I couldn’t believe the notifications on my phone—even the mayor had commented on my post. I was blown away that I could get his attention and that he would feel compelled to respond. The next day, on Good Day LA, they were showing my art during a segment on homelessness and cut to a speech from the mayor. People contacted me assuming that my artwork was the motivation for the address—which may not be the case, and it’s not my intention to be a thorn in the mayor’s side. But got me to start thinking about how I can make a more lasting impact.

What would that look like—a more lasting impact?

Currently I’m doing an exhibit at an architecture firm in Long Beach called Studio 111. They do a lot of urban and community development in that area, and I’ve started working with them to imagine a new style of container housing. As it stands, when the city proposes a “shelter,” it’s immediately off-putting to the surrounding community. I understand, because people should have a right to know who is moving in and there should be some sort of transparent screening process that they have access to. Rather than addicts or people with psychiatric diseases, many of the people who can benefit from low-income housing are single parents or individuals have one or more jobs, but the economy prevents them from getting a traditional apartment. We believe that if these communities were presented as art-centric, it would be more interesting for both the people who would live there and the existing neighborhood.

In the cases where residents do need some sort of rehabilitation, I also think it would be helpful if we developed communities that are specific to each addiction. I don’t see it as highly efficient to have alcohol and meth addicts, for example, recovering side-by-side. When a community shares the same struggle, it’s easier to create genuine empathy and support. It’s not just about a handout—the focus should be reconstructing lives.

You said that when you first started this work, it was because you were dissatisfied with the state of street art. How does your art continue to reflect that perspective?

Art has always been a reflection of the times, a major part of revolutions and a way to transform our world. But over the last decade, art has suffered. Street art has become a medium where non-talented individuals can appear to have more talent than they do. Today, you see people getting out of art school with degrees, and instead of going into advertising, they now go into street art. If their work plays off of something that people are already familiar with—say, The Beatles—people will consume it and it becomes a “hot tip.” But I come from much grimier soil in terms of my graffiti. It isn’t about commercialism. I believe that art should have something to say.

2

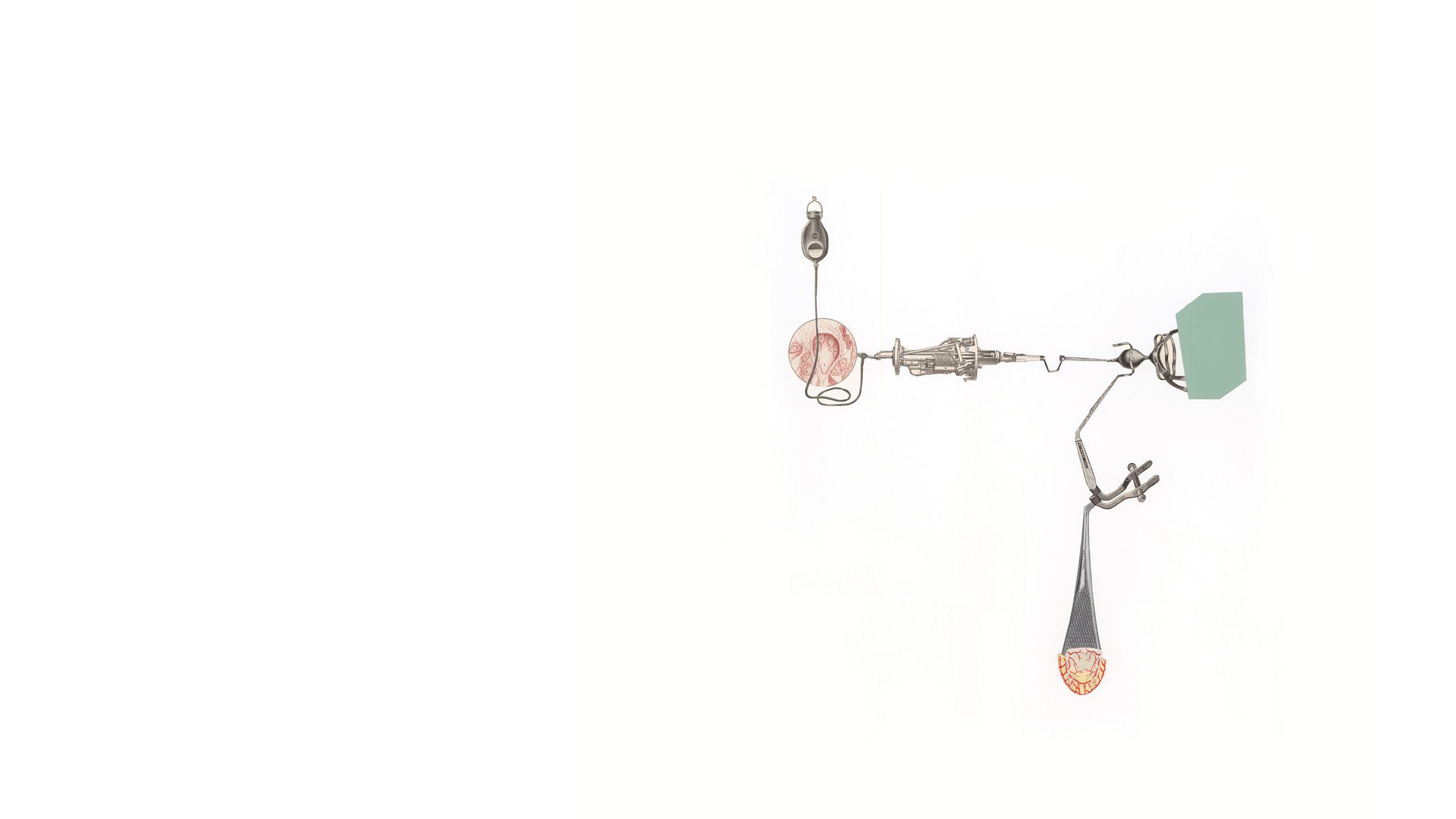

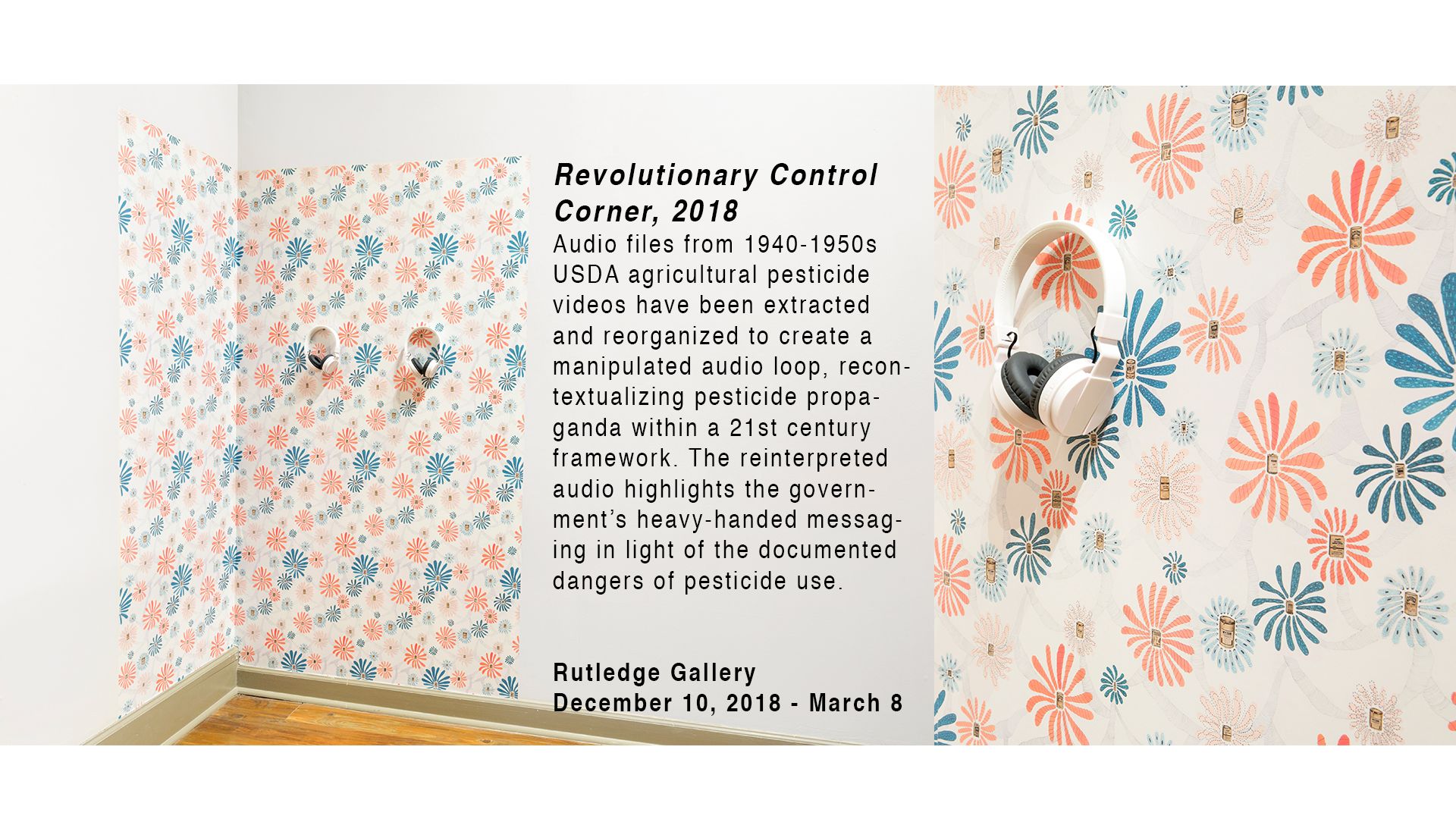

Kirsten Stolle

is an Asheville, North Carolina based visual artist working in collage, drawing and mixed media. Her research-based practice is based in the investigation of corporate propaganda, food politics and biotechnology.

Stolle’s work explores the darker side of American agriculture, using collage to reveal challenging contemporary perspectives on practices including GMOs and the widespread use of pesticides. In MONSANTO INTERVENTION, she repurposes Monsanto Chemical Company advertisements, exposing the true threat posed by this propaganda and weak government regulations on corporate agribusiness. In ANIMAL PHARM, her collages play off Orwell’s dystopian fable, exploring the role of pharmaceuticals and corporate influence over national agricultural practices. Finally, in REVOLUTIONARY CONTROL, she extracts audio from 1940-50s USDA pesticide videos, manipulating it into a looped, auditory collage that contrasts this heavy-handed messaging with the documented dangers of pesticide use.

3

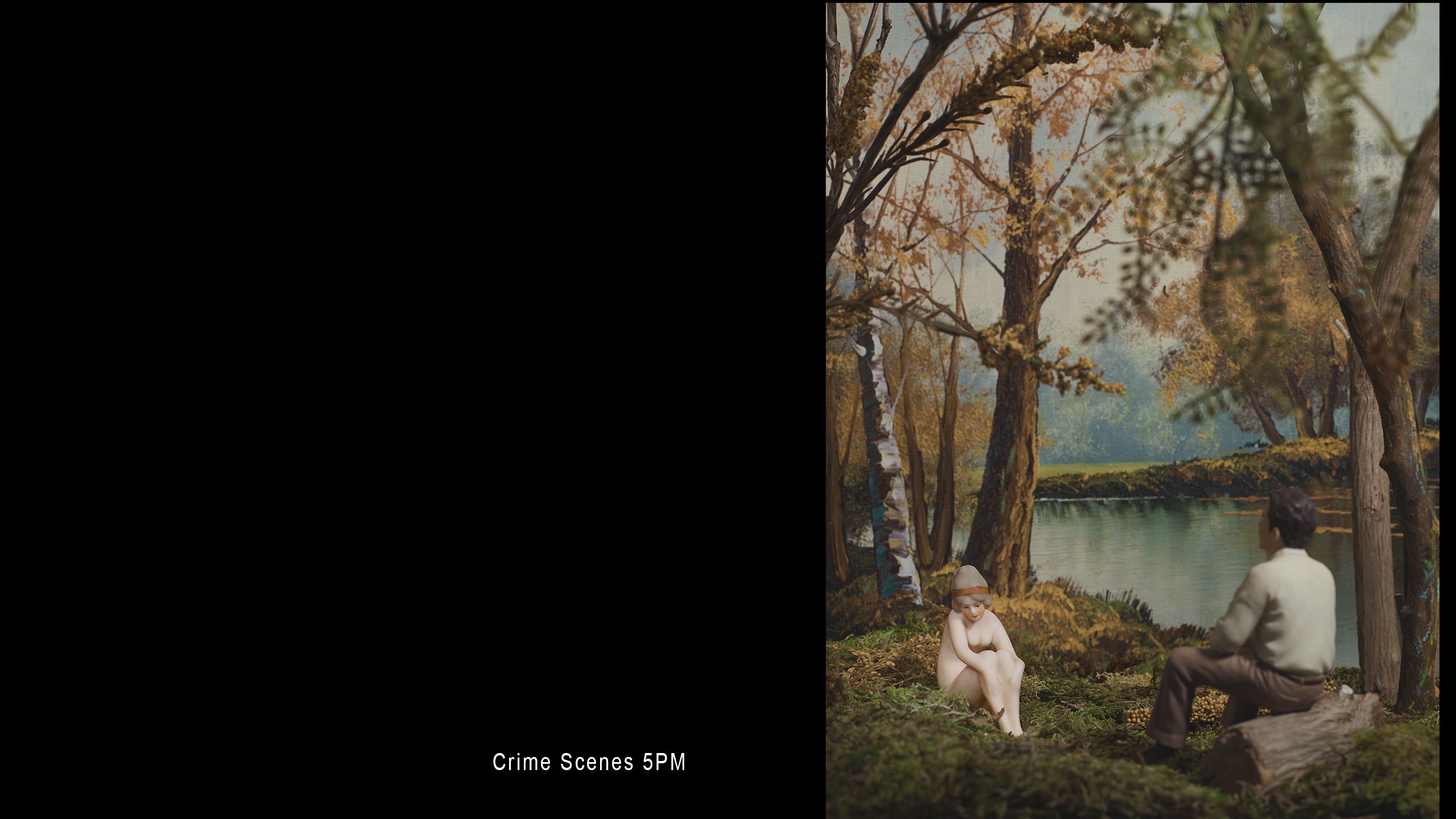

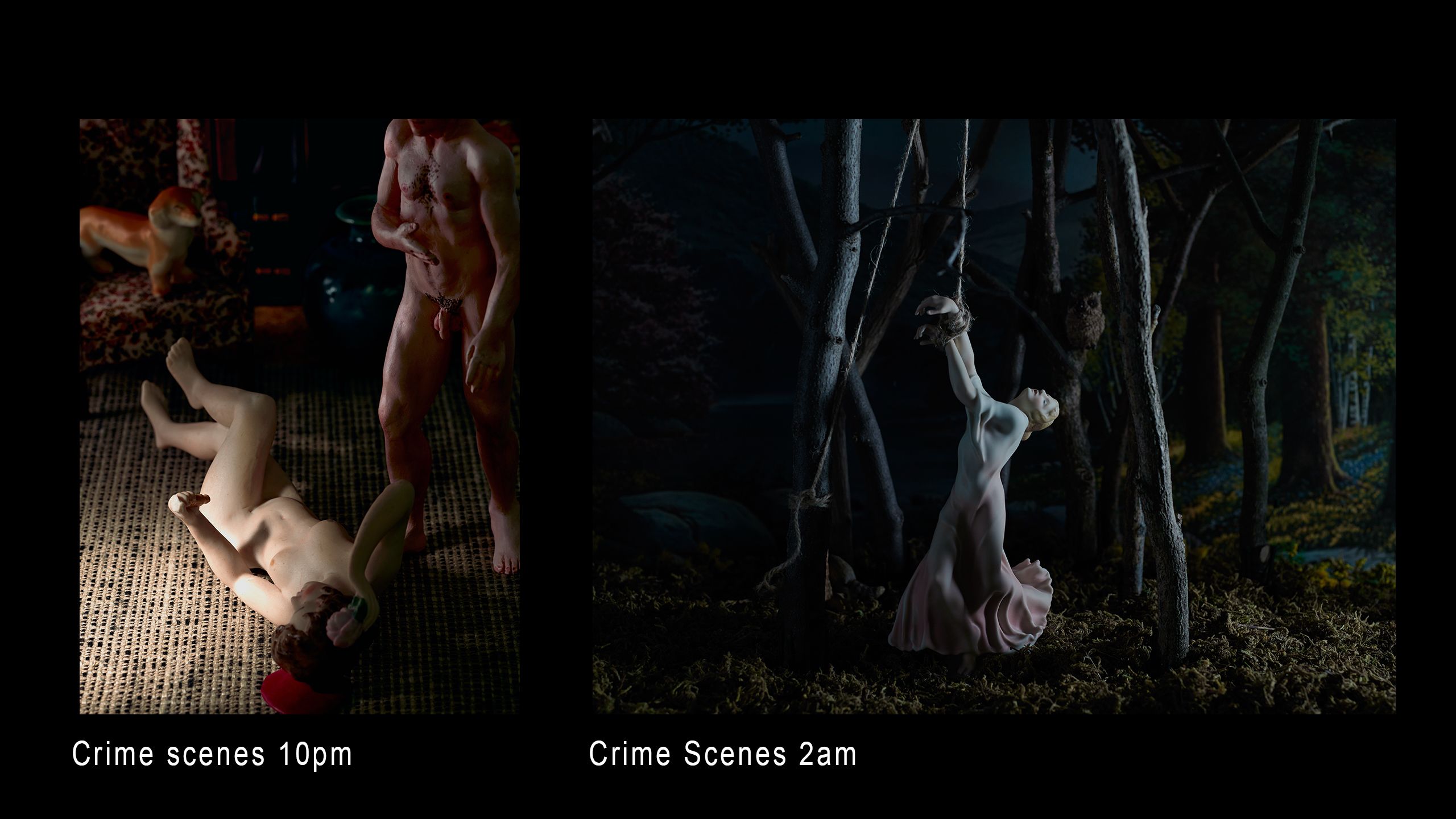

JUDY LIPMAN SHECHTER + DAVID SHECHTER

Based in New York City, Judy Lipman Shechter is an assemblage artistand David Shechter is a fine arts photographer. Their collaborations integrate serious contemporary topics into fantastical images that captivate and challenge the viewer’s assumptions and perceptions.

In this photographic collaboration, the emotional aspects of the crime have been removed from each image. These are not real people; there is no pain, fear, dread, remorse or regret. This disassociation allows the viewer to linger as an observant voyeur, discovering details that beg the question: “Are you a witness to a crime or misinterpreting the moment?” In turn, as the viewer considers what they are perceiving, they must simultaneously confront that which draws them in and that which makes them uncomfortable.

5

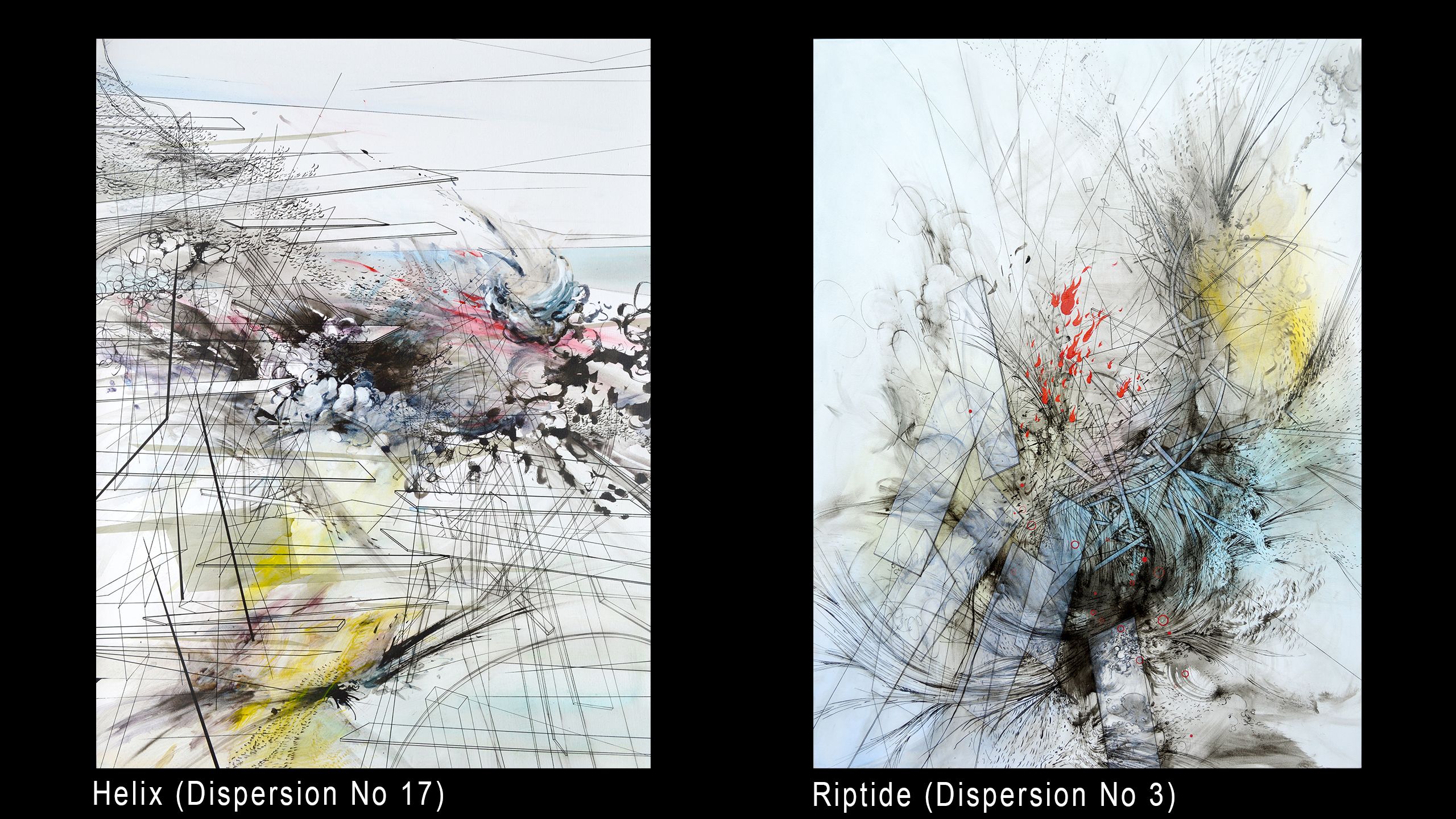

Chee-Keong Kung

is a Singaporean artist based in McLean, Virginia. His evolving visual vocabulary draws from the media and contemporary culture, as well as observations of natural and man-made environments

Kung is interested in the emotive resonance that springs from the act of seeing and remembering. His works evolve over time, often set aside for days until his next move becomes clear. This “Dispersion Series” was created through alternating layers of intuitive gestures and precise geometry, continuing until each work appears to hover between perfection and imperfection, gravity and weightlessness. For certain paintings, the trajectory of the work was defined early on; yet Kang often finds his most satisfying works lead him to entirely unexpected places.

6

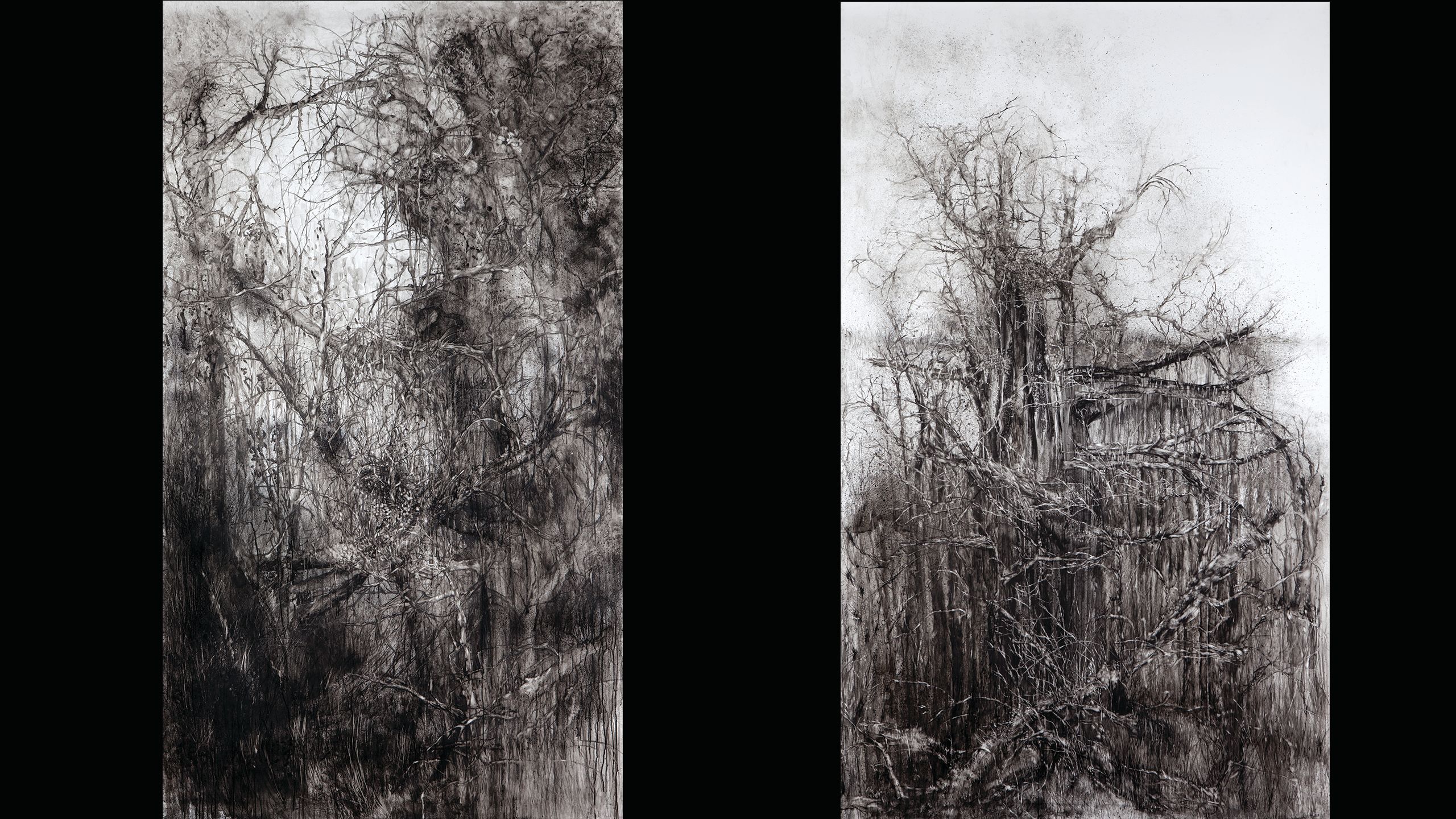

MARGERY THOMAS-MUELLER

Mueller’s work has been deeply impacted by the poetry of Edna St. Vincent Millay, specifically Renascence, which speaks to the space between one’s state of being and how we treat each other. Her abstract landscapes convey this “world in between,” expressing an empathy for the challenges and circumstances of the other. The uprooting of humanity informs her landscapes, rich with branches, thickets and thorns. Her choice of Yupo paper—whose waterproof quality allows it to be erased with a simple stroke of water and ammonia—mirrors the instability and constant flux of our natural environment.

7

Geir Moseid

A Norwegian photographer based in Oslo. Working with a 4x5 camera, his use of both documentary practice and staged photography aims to challenge how one can discuss social, anthropological and economical issues through contemporary images.

8

Sean Gall

Sean Gall is an American artist currently living and working in Rome, Italy. His work in drawn ink and painted patterns explores the themes of wandering and urban sprawl—walking, exploring and getting lost.

These mind-scape drawings and urban sprawl paintings are inspired by environments as diverse as Gall’s original home in Los Angeles, his mother’s roots in the rugged landscape of Western Ireland or his adopted city of Rome, Italy. The surface is initially approached by either the layering of obsessive details or one horizontal line across the entire canvas. Repeating these elements across the picture plane, slight variations add to the pattern and reflect the visual landscapes of mountain ranges and urban centers alike.

9

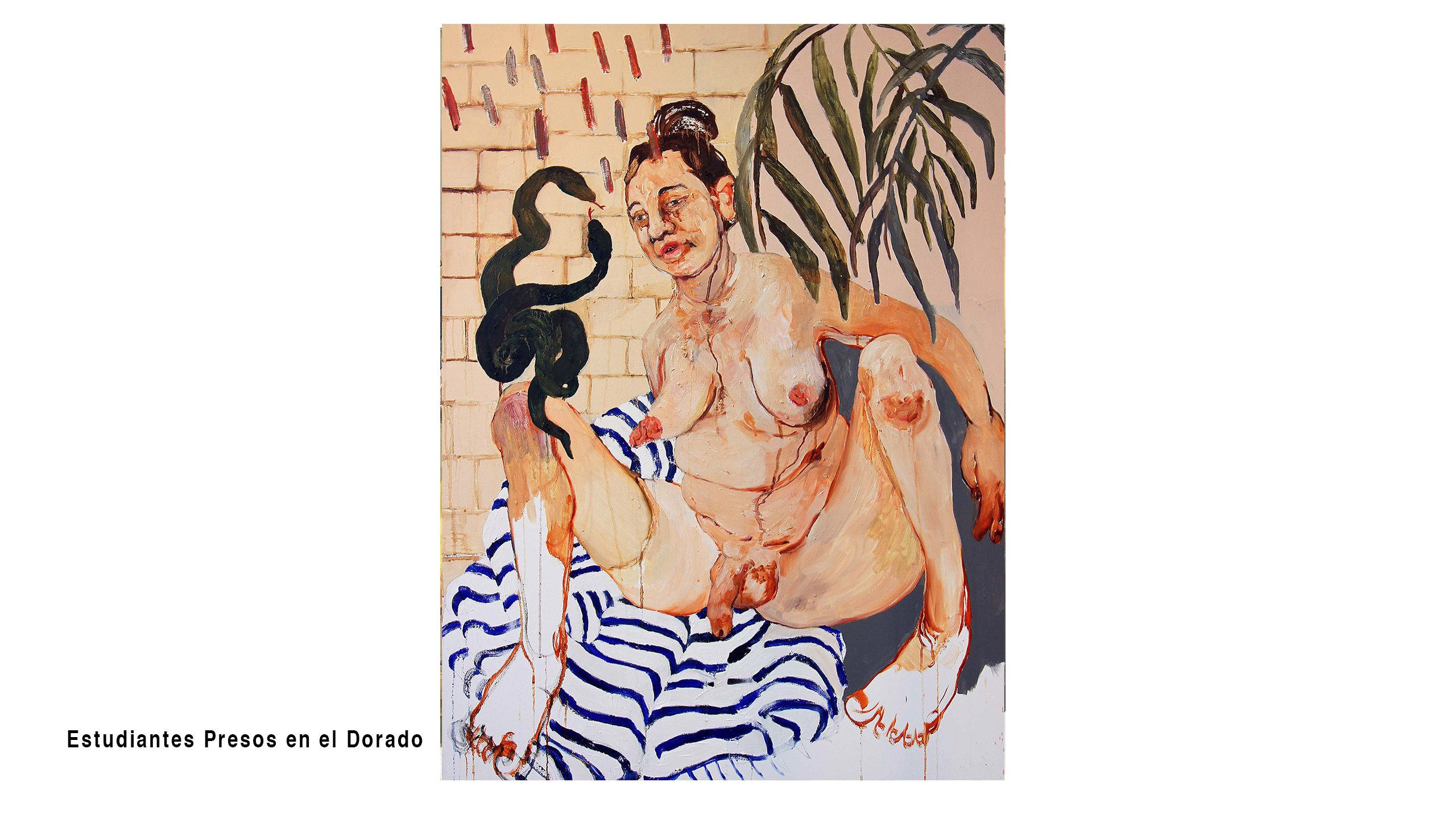

Bernadette Despujols

is a Venezuelan artist currently living in Miami, Florida. Exploring and questioning the perception of women, sex and contemporary life, her practice incorporates such varied media as painting, sculpture, video and installation.

TBC / MAG

is a platform for emerging and mid-career artists. It is a semi-annual digital and print publication for curators, galleries and art enthusiasts. We are an extension of The Billboard Creative, a nonprofit platform for both emerging and mid-career artists. We work to help artists breakthrough traditional career bottleneck, providing unprecedented exposure to a mass market, by transforming commercial billboards into public art sites. This representation both raises the profile of individual artists with the general public, and introduces new works to curators, galleries, and passionate art enthusiasts.

FOUNDER/EDITOR: Adam Santelli / Kim Kerscher

WORDS BY: Carly DeFilippo

SUBSCRIBE / SUBMIT: thebillboardcreative.org

CUSTOMER SERVICE: archie@thebillboardcreative.org

INSTAGRAM: the_billboard_creative

TWITTER: @tbcbillboards

All Image copyrights are held by the Artists that created them.